July 31, 2017

The Heat Wave of 1936

People love to talk about the weather. Maybe it’s because with friends or strangers alike it is, in our controversial world, a safe topic to broach. The month of July certainly brought us much fodder for conversation with some pretty hot temperatures spawning serious storms and flooding from Chicago to St. Louis. While watching the weather news each day I noticed that even though the temps were high, the record temperatures of 1936 still held the record. To quell my curiosity I decided to do a bit of research; what I found was article after article on the “The Heat Wave of 1936”!

On July 14, 1936, Iowa reported readings of more than 108°F at 113 separate weather stations. The chief of the Iowa Weather and Crop Bureau called July 1936 the hottest July in 117 years. The heat wave of 1936 broke all records in 15 states during July and August and was the final blow to many mid-western farmers who had fought against economic hardship and unparalleled heat and drought.

In the vast Dust Bowl region that spread from North Dakota southward into Texas, with its heart over Kansas and Oklahoma, black-dust blizzards had been common since 1932, but the 1936 heat gave new energy to the asphyxiating dust storms that blackened skies. Trains missed their scheduled stops because they couldn’t see the towns through which they passed. Doors and windows had to be sealed with adhesive tape to keep out the dust. Dishes had to be washed after a meal and again before the next one because dust sifted into cupboards. Ceilings collapsed from the weight of dust that had collected in attics. Seeded crops blew out of the soil, and white chickens were dyed the color of dust.

Kansas City, Missouri, saw temperatures of over 100°F on 53 days that summer. Parts of Kansas and North Dakota soared to 121°F; South Dakota, Arkansas, Texas, and Oklahoma saw 120°F. Indiana, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Jersey, West Virginia, and Wisconsin also hit their record highs in July or August of 1936.

Other parts of the country were also affected by the hot temperatures. Even on the “cool” eastern seaboard in July of 1936, it was the heat wave that made the news. Waterbury, Connecticut, saw 103°F, while many other New England towns hit over 100°F. On July 9th, Central Park in New York City hit 106°F. In New York City, mayor LaGuardia declared public beaches open all night for the duration, promising not to arrest anyone. City swimming pools lengthened their hours. People who were able left the steaming asphalt of the cities; those remaining stood under sprinklers or slept on roofs. Nearly 5,000 deaths nationwide were attributed to the heat wave; some from heat stroke or lung ailments; others from accidental drownings, as non-swimmers desperately tried to cool off.

One of the most interesting articles I found during my research was the following accounting of Davenport, Iowa in the summer of ’36!

“1936 was a year of extremes not only socially and politically, but for weather as well. As the U. S. continued to struggle through the great depression, the winter of 1935 – 1936 brought record-breaking bone chilling cold while the summer saw record-breaking heat strike most of the country. Davenport was no exception. Many of the high temperature records set that summer still stand. Drought, grasshoppers, floods (in specific areas), and tornados also added to the natural disasters of the year.

Drought was beginning to plague this region as temperatures began to rise in late June 1936. Cooler weather returned briefly until July 5th when the temperature reached 105 degrees. On July 6th it was 105 degrees again and The Davenport Democrat and Leader evening addition reported the first local heat related death, Mr. Leo Brandmeyer age 32 of Rock Island. The overnight temperature dropped to only 81 degrees before soaring again to 105 degrees on July 7th. The Davenport Democrat and Leader reported that day the difference in temperature between January 1936 (low temperature of 22 degrees below zero) and July 7h, 1936 (105 degrees) was 127 degrees, a new record temperature swing for one year. That record would be surpassed in only days.

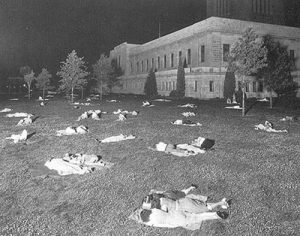

Between July 5th and July 15th the temperature remained above 102 degrees during the day with temperatures only dipping into the 80’s at night. The highest temperature came on July 14th when the thermometer hit 111 degrees. With no rain in sight newspapers began to report on crops dying. Adding to the agricultural distress were grasshoppers eating what crops were not withering away in the sun. Only a few hotels and movie theaters had air conditioning. Home cooling systems were still very rare. Families began to live in their basements during the day to keep cool. At night people slept in parks or on lawns trying to find what little comfort there was in the outdoors. The local papers continued to list those who had either died or collapsed from the heat.

Between July 5th and July 15th the temperature remained above 102 degrees during the day with temperatures only dipping into the 80’s at night. The highest temperature came on July 14th when the thermometer hit 111 degrees. With no rain in sight newspapers began to report on crops dying. Adding to the agricultural distress were grasshoppers eating what crops were not withering away in the sun. Only a few hotels and movie theaters had air conditioning. Home cooling systems were still very rare. Families began to live in their basements during the day to keep cool. At night people slept in parks or on lawns trying to find what little comfort there was in the outdoors. The local papers continued to list those who had either died or collapsed from the heat.

In the midst of the heat wave, life went on with 1936 being the year of Davenport’s Centennial. A huge celebration took place including a Centennial parade which drew an estimated 10,000 people on July 14th. The Daily Times printed a 144 page special edition on July 11th to celebrate the Centennial. One person featured was Henry P. Brown a Civil War veteran and G.A.R. member who had been appointed in April 1936 as aide-de-camp for the National Commander of the Grand Army of the Republic. Mr. Brown would become a victim of the heat on July 15th. On July 16th the temperature finally fell under 100 degrees during the day for the first time in fourteen days with an evening temperature in the 70s. July 17th saw another record breaking day, but by July 20th the heat wave had broken and rain began to cool the area. The evening temperature even reached 67 degrees, the coolest temperature since July 3rd.

An estimated 89 people died locally during the 1936 heat wave. Interestingly, the excessive heat was not located in the southern U.S., but in the northern and Midwestern regions. Warmer weather did return, but in spurts intermixed with cooler temperatures as well. The long continuous heat did not come back. A large percentage of crops were lost that year which added to the misery of the depression. Even the Mississippi River was hit hard as it dropped to 1.0 foot below normal on August 15th, 1936, its lowest recorded level in the Quad City region. This surely was a summer to forget, and most definitely not one to repeat.”

As we experience the remaining hot summer days in our air conditioned offices, cars, and homes, imagine for just a moment what our ancestors might have dealt with during the heat wave of 1936!

Mary Schricker Gemberling

Mary, a former educator and Seniors Real Estate Specialist is the author of three books, The West End Kid, A Labor of Love; My Personal Journey through the World of Caregiving, and Hotel Blackhawk; A Century of Elegance.

Filed Under: History

Trackback URL: https://www.50pluslife.com/2017/07/31/the-heat-wave-of-1936/trackback/